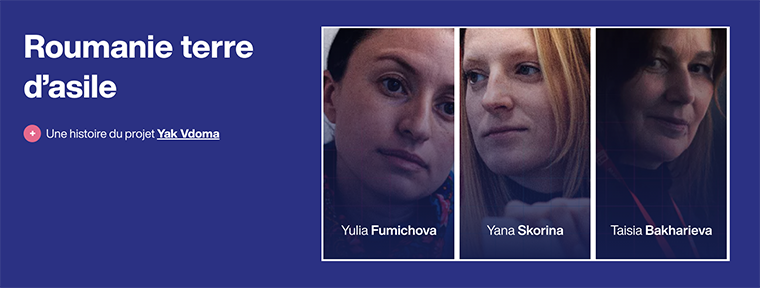

Yulia Fumichova, drawing inspiration from women

Yulia Fumichova is forging links between Ukrainian women currently scattered around the country and across the whole of Europe. She is also giving them a voice in a nation where the move towards gender equality is picking up pace.

Yulia has never taken maternity leave. Both times she gave birth, she never stopped working while in hospital. Her two little girls have become accustomed to watching her glued to her computer or on the phone. "Whether we're here in Bucharest or elsewhere, it doesn't make much difference to them in truth, they've always been with me 24 hours a day", Yulia explains, casting a protective eye over 7-year-old Nadia, who is reading at a table, and her little sister Veronika, who is doing her utmost to prevent her. Yulia takes them everywhere because, like so many others, she is bringing them up alone. Used to moving with the conflict, the 34-year-old mother is the wife of a soldier who has been at the front since 2014.

Yulia is no stranger to the front line herself either. Until Nadia and Veronika were born, she used to report from there. Although she has since moved away from the front physically, she has never stopped reporting on it, serving as a voice for those fighting there. A native of Cherkasy, a city midway between Kiev and Dnipro, and with 15 years' experience as a war reporter, Yulia's determination guides her work more than ever.

Yulia exudes an impressive sense of serenity, in stark contrast to everything she has experienced and tells us about. While being in Bucharest soothes her – her youngest daughter always saying, "here, we can get a break from the alarm", – all those years in contact with the war have undoubtedly taught her to keep a grip and control her nerves. You get the feeling that knowing she and her children are safe gives her a welcome breath of fresh air. "I hope to return to Cherkasy, that's where I want to be, but I'll only do that when it's no longer a dangerous place for me and my children." With no water, electricity or reliable internet, it's more than complicated to work from there at the moment.

Heroines in the face of conflict

In her day-to-day life, Yulia can spend a whole day talking on the phone or on social networks with one of the women whose experiences she recounts. "Many of them need to open their hearts, and they often start crying mid-sentence, when a memory resurfaces or reality suddenly rears its ugly head," explains Yulia, who regularly calls on psychologists to make sure she understands the women properly and is taking the right tack.

"Sometimes, I'm the one who needs a psychologist," admits the journalist, who at times can feel as if these women's words and stories, "slice through her body." Despite her best efforts, Yulia admits to feeling "like a sponge" and finding it hard to protect herself. "It's hard because this country under bombardment is mine too," she almost apologises.

Most of these women have the burden of a broken family in common, whether they have stayed in Ukraine or gone into exile in other countries. Like her fellow resident Taisia, Yulia also calls them her "heroines". Each as magnificent as the other in her eyes.

"There's the teacher who refused to teach Russian in occupied territory, and all the wives of dead or missing soldiers who must start again from scratch with no one to support them, those who have left their cosy workplace to go and do voluntary work at the front, others who have travelled thousands of miles from home with just a rucksack on their back and their child in their arms," Yulia continues, with composure.

She often supplements her articles with a side column in which she recounts her personal life, "to show them that they're not going through all this alone." In Bucharest, her ambition is to supplement her work with video interviews with doctors and psychologists, to supply her readers with essential information about how to provide basic care, how to disinfect water, how to obtain psychological support, etc. - and to give them a chance to express their opinions.

Gender inequalities persist, even in wartime

And then there's the front line, where many of them are. "With all the discrimination that implies," recognises Yulia. Disregarded, victims of harassment, "they have to fight against that too," adds the journalist.

Do Ukrainian men consider Yulia's heroines to be cut-rate? "It's true that some people will always tell you that a woman's place is in the kitchen," admits Yulia, who nonetheless believes that her country is currently changing on these issues. "It had started before, but has sped now. Women's involvement in the military effort has changed attitudes," says the young woman, who is delighted to note, with statistics to back it up, that her articles are actually read more by... men. "Touched by what they're doing and have endured during the conflict, many men now see them as real heroines," says the journalist with satisfaction.

She ends with a story about Elizabeta, a young woman from Kiev who has been six months without news of the man she hopes one day to marry. He has gone to the front. "While waiting for him, she works on the songs he was writing before he left and exhibits his paintings. She looks after his mother. For me, this young woman is a rock, she has so much strength."

Yulia believes that it's "this type of story, both beautiful and poignant, that brings all Ukrainians together today."

Des inégalités de genre qui persistent, même en temps de guerre

Et puis il y a le front, où beaucoup d'entre elles se trouvent. « Avec ce que cela implique comme discriminations pour elles », lâche Yulia. Déconsidérées, victimes de harcèlement, « elles doivent se battre contre ça aussi », témoigne la journaliste. Les héroïnes de Yulia seraient des héroïnes au rabais pour les hommes Ukrainiens ? « Une partie vous dira toujours que la place de la femme est à la cuisine, c'est vrai », avoue Yulia qui estime toutefois que son pays opère actuellement sa mue sur ces questions. « Cela avait commencé avant mais là tout cela s'est accéléré. L'implication des femmes dans l'effort militaire a fait évoluer les mentalités », juge la jeune femme, ravie de constater, statistiques à l'appui, que ses articles sont en réalité davantage lus par... des hommes. « Touchés par ce qu'elles font et endurent pendant le conflit, ils sont désormais nombreux à les percevoir comme de vraies héroïnes », se réjouit la journaliste.

Elle termine avec Elizabeta, une jeune femme de Kiev qui attend celui, parti au front, qu'elle souhaite un jour pouvoir épouser et dont elle n'a aucune nouvelle depuis six mois. « En l'attendant, elle travaille sur les chansons qu'il écrivait avant son départ et expose ses peintures, tout en s'occupant de sa mère à lui. Pour moi cette jeune femme est un roc, elle a tant de force ». D'après Yulia, c'est « ce type d'histoires, belles et poignantes à la fois, qui rassemblent tous les Ukrainiens et les Ukrainiennes à l'heure actuelle ».