Olena Dyachuk, education in times of conflict

A journalist specialising in education issues, Olena Dyachuk observes the difficulties of a system stretched to breaking point by the war.

Olena Dyachuk admits that, in hindsight, she was "dead wrong" about a specialisation she considered potentially "boring" in 2017. It is now clear for the journalist that "one of the serious consequences of this war is that the country no longer has any normally educated young people. It's going to take us many years to catch up," notes the 32-year-old, reluctantly. The former copywriter, who has been working on education issues for the past five years, is a close witness to the efforts of a Ukrainian education system that is struggling to survive.

Sporting glossy burgundy hair, Olena is clearly enjoying her return to normality in the Romanian capital. Born in Snizhne, not far from Donetsk, her region was occupied as early as 2014 and she had to go into exile in Karkhov. It was there that she saw the advertisement for a job as a journalist with a local publication specialising in education. She spent eight years in the region before the Russians arrived. Forced to flee once again, she left for Poland, where relatives of hers were already living, and where she settled for six months. Since last October, Olena and her mother (and their cat) have been living in Bucharest. The trio may stay longer than the six months they originally planned: "It's become so hard to plan for the future," admits the young woman in a small voice, worn out by moving country so frequently.

A subject brought to light by the conflict

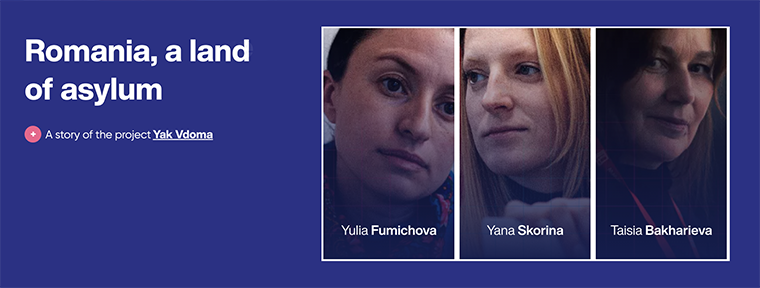

As part of the Yak Vdoma project, Olena mainly writes articles and conducts interviews with teachers and those in charge of the Ukrainian education system. The publication she works for was already one of the rare few to tackle these issues five years ago. Since the war, it has become even more complicated, with – unsurprisingly – many redundancies among journalists in the sector. As for the reality in schools, we quickly understand Olena's frustration, as she lets out a long, heavy sigh, feeling "deeply sorry that Ukrainian schools have been reduced to this situation."

Lacking electricity, lighting or heating, dealing with incessant alarms or constant attacks... the closer the schools are to the front line, the greater the constraints and risks.

"It's very complicated, I feel sorry for the teachers, the pupils and the parents, but even in the bunkers things are organised so that the pupils can learn," explains Olena, who plainly knows that some teachers actually work 24 hours a day. They're exhausted," she says.

"We can no longer speak of a normal work schedule, especially as these teachers have, in a way, come to take responsibility for the children's lives," continues the young woman with emotion. Her voice trembling, she recalls the online competition she organised in 2022, in which many children took part from bunkers. "Everyone was saying it was fine, that it wasn't that dangerous, whereas we, the adults who read their work, knew very well that it was. We had somehow taken the tragic dimension of what was happening to another level," recalls Olena, who sometimes struggles to express some – still vivid – memories.

Destroying the Ukrainian education system, a strategic priority for the Russians

To describe Russia's demolition of the Ukrainian education system, the journalist is blunt, describing it as "a systematic and programmed attack aimed at total destruction."

"If they don't occupy a city, they'll give priority to bombing the schools, but if they're there, their aim will be to use propaganda to completely upturn education," explains Olena. The figures are unequivocal: 3,000 educational facilities (nurseries, schools, universities, etc.) have been destroyed since 24 February 2022.

You can tell that the theme of education, which she deplored as boring in 2017, has taken on a whole new meaning for the young woman in the current context. Her first reaction is to say that the authorities should be so doing much more, that "it's an emergency," but Olena nevertheless prefers to take a positive view, given the conditions.

"Many people expected our education system to collapse completely, but it's holding up," she states, proudly. In fact, 7,000 schools were opened last September for the new academic year, each with its own set of comprehensive safety rules. "3,000 others have not been able open due to the lack of air raid shelters," she regrets, aware of all the children who are studying online in their town, or far from home in a foreign country. "It's as if time were suspended for a whole generation," she sighs.

Heroic teachers

Time may feel suspended, but many spend it resisting. For Olena, "language is the key. Young people have understood this too, especially those who have been exposed to Russian propaganda," she explains.

After leaving Donetsk, Olena also lived in the town of Balakliia to the south of Karkhov, where she forged links. After she left, teachers told her about the occupation and the Russians forcing them to change their curriculum. "They agreed to do so, but were able to save a few books behind the backs of the Russians, who were destroying Ukrainian textbooks. It was really dangerous; you could be tortured for it. But thanks to their courage, they were able to continue following the Ukrainian programme online and in secret."

Olena refers to them as heroes, "it was top secret, no one was allowed to talk about it. This went on for two months, before the Ukrainian army liberated them. It makes me want to cry when I think of how brave they all are," admits Olena. “Many schools would have done the same thing," she assures us.

Some didn't make it through the liberation. "In some places, teachers disappeared. From one day to the next, there was no news of them," sighs the young woman for the umpteenth time.