Survey

Representing migration in the media

Produced in 2023

Report on capacity-building initiatives and recommendations

In brief

This participatory study, carried out within the framework of the Dialogues migrations project, was conducted to identify the actors and actresses acting in the media and on migration, to understand and analyze the representations conveyed by the media discourses and the public discourses relayed in the media and social networks on migration. It draws up an inventory of the actions already deployed by other international operators and analyzes their impact.

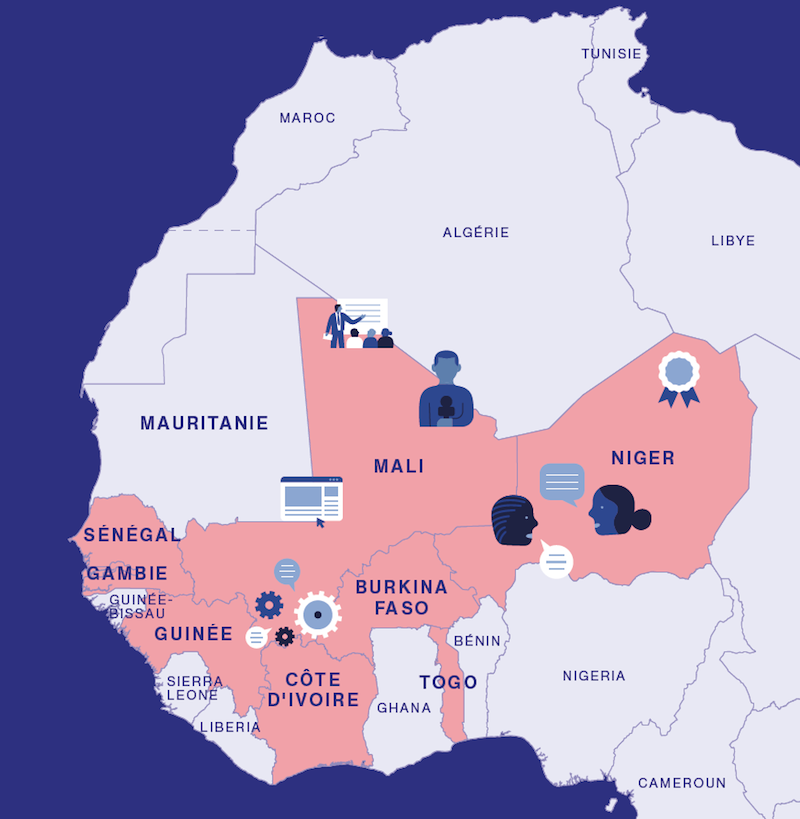

It covers the period from January 2015 to March 2022 and studies sixteen countries: Burkina Faso, Colombia, Comoros, Ivory Coast, Gambia, Guinea, Jordan, Lebanon, Madagascar, Mali, Morocco, Mauritania, Niger, Senegal, Togo and Tunisia.

Summary

In April 2021, CFI thus launched the “Dialogues on Migration” project, funded by the French Ministry of Europe and Foreign Affairs (MEAE). The project aims to help foster an inclusive debate across society to bring about change in how migration is represented in the public arena. As part of this project, pilot activities to build capacity in production on the theme of migration were launched in 2022, targeting media outlets, journalists and schools of journalism in the Gambia, Guinea, Mauritania and Niger. 1 This report was also commissioned for this project, as part of a forward-looking approach aiming to assess the pertinence and opportunity of developing projects to reinforce media outlets and support them in providing well-informed, well-balanced coverage of migration, alongside the French development agency (Agence Française de Développement or AFD) in particular, in one or several of the countries under review.

This participatory assessment has been conducted to pinpoint stakeholders in media and migration, gain insight into the representations conveyed by both media and public discourse relayed in the media and social networks on migration, analyse these representations, draw up a comprehensive report of initiatives already deployed by other international operators and analyse their impact It covers the period from January 2015 to March 2022 and examines 16 countries: Burkina Faso, Colombia, Comoros, Côte d’Ivoire, the Gambia, Guinea, Jordan, Lebanon, Madagascar, Mali, Mauritania, Morocco, Niger, Senegal, Togo and Tunisia.

Three organisations were selected to produce this report: the DARA International foundation and DAHLIA, which reviewed Colombia, and consulting firm Red Mangrove Development Advisors (RMDA)), which reviewed the other 15 countries. This report is the outcome of the work to standardise the reports produced by these three organisations on the 16 countries under review. With a view to standardising the document, CFI modified it after the transmission of the finalised versions, with upport from the Steering Committee comprising the MEAE, AFD, and the organisations tasked with producing the report (RMDA, Dahlia and Dara).

The main expected results

The main expected outcomes of the report were to:

- gain insight into the image of migration and migrants in both media and public discourse in the 16 countries via an overview outlining the key migration trends, and a review of how migration is handled in both the media and public discourse,

- identify what has already been done and who by, in terms of building capacity in the media on the theme of migration in these 16 countries, and the ensuing impact with: a report on capacitybuilding and support initiatives conducted, and an assessment of their impact, and possible courses of action for CFI, its partners and other organisations providing support to media outlets with an interest in this theme.

The same method was applied across the board to all countries, with a literature review, one-on-one interviews, a discussion group with migrants and another with journalists having benefited from capacity-building projects. Each discussion group was attended by around ten participants, the main aim being to collect and analyse their perceptions of media coverage of migration in their country of residence.

The aim of the journalist discussion group was to collect their assessment of the capacity-building initiatives they had previously attended and analyse this.

The interviews were based on common guidelines applicable to all countries and targeted the following persons:

- media professionals (chief editors, journalists specialising in migration issues, representatives of media regulation bodies etc.),

- professionals working in migration (associations, international organisations, research institutes etc.),

- partners and stakeholders committed to professional, responsible media coverage of migration (government bodies, technical and financial partners, schools of journalism, international organisations etc.).

15 to 30 interviews were conducted, depending on the number of pertinent stakeholders identified in each country.

The country reviews were each produced using the same outline and the same predetermined terminology and tools for the purposes of comparing countries and to foster interregional and international prisms of thought.

The report uses internationally defined concepts, even though this terminology is often far removed from actual conditions on the ground and the vocabulary of journalism. Migration is a complex phenomenon, with certain forms tending to overlap, both from a conceptual and statistical vantage point. For example, those of us living in the west can have trouble distinguishing between economic and family migration.

Each country review was produced by a team comprising members of the international coordination team with one or two local consultants, using shared tools and the vocabulary and context specific to each country. The report will be followed by a communication campaign and the organisation of a forum at which the findings of the report will be shared, to raise awareness among local and international stakeholders and to identify possible links and synergy in action.

Media landscape

Traditional media (television, press and radio) are all available in varying proportions and volumes in all 16 countries included in this report. To cite an example, Morocco has a rich media landscape with some 60 newspapers and magazines, whereas neighbouring Mauritania only has five.

In most of the countries in West Africa and Comoros, national and community radio is also very important. As evidenced by Côte d’Ivoire with around 200 radio stations of various types: nationwide public stations or privately-owned stations; the remaining radio stations mostly serve local communities.

Social networks’ reach is growing in the media landscape. In matters of migration, these networks are used in three separate ways:

- Facebook, WhatsApp and Viber are commonly used by migrants themselves to communicate with others and to collect information on migration;

- these networks are also a source of useful information for journalists covering migration issues;

- lastly, they act as a “sounding board” for public and media discourse, providing an arena for personal accounts and more radical opinions on migration (not necessarily well-founded).

The freedom of information

Lastly, in certain countries, the freedom of information is greatly restricted, which in turn impacts media coverage. For example, Reporters Without Borders (RSF) specify on their website that in Morocco, “Independent media and journalists are subject to tremendous pressure, and the right to be informed is crushed by a powerful propaganda.

The situation in Colombia is detrimental to the media, with reporters being subjected to physical assault, death threats and assassination 2. In other countries such as Lebanon, the media coverage of migration is impacted by a highly concentrated, politically polarised media landscape.

Migration in media and public discourse

The report examines the representation of migration in media discourse and, to a lesser extent, public discourse.

The notion of public discourse is broad, embracing statements by political officials and public personalities, media content, and also members of the general public who express their views, mostly on social networks. The notion of media discourse is more restricted in scope, embracing all output emanating from professional news outlets, whether in print or online, on television or radio. Despite media diversity and the fact that outlets exercise a certain degree of independence, media discourse still tends to act as a sounding board for public discourse.

It has transpired from the interviews that the topic of migration is sometimes handled patchily – with attention focused on certain types of migration – or loosely. These observations echo the discussion groups, in which migrants declared that they did not feel that the media represented them accurately.

One cause of partial, low-quality coverage resides in the reasons for the media focussing on migration, in that the topic of migration is mostly addressed depending on:

- the news. News coverage mostly features dramatic events involving irregular migration. This is a “clickbaity” theme as well as being a core issue to raise awareness of the dangers in connection with irregular migration. In Comoros for example, out of a sample of eight journalists interviewed on the subject of the media coverage of migration, five mentioned losses at sea in the kwassas heading towards Mayotte and the shipwrecks between Morocco and Spain 4, emphasising that these dramas are the only migration events to be given media coverage. Articles examining in-depth causes and stakes, or other forms of migration, are simply non-existent;

- institutional communication by states and international institutions that help migrants. The media discourse actually relays public discourse. On this point, while the report only focusses on countries in Africa, Latin America and the Middle East, links with Europe and other “northern” countries are very often mentioned in the country reviews:

- communication from national institutions is often influenced by national migration policies, especially when governed by bilateral agreements with European Union (EU) countries. Thus, since 2015, Niger has evolved from a role as a migration corridor to that of a pivot country, by becoming a key EU partner in the monitoring of migration routes 5. In the discussion group meetings, journalists explained that the media in Niger very often repeated the Nigerian authorities’ viewpoint and the local EU representation of migration, with the result that they themselves were also focused on irregular migration, and related tragedies and consequences such as voluntary or forced returns;

- communication from international institutions to help migrants are strictly controlled by these same organisations for both information and advocacy purposes. In Burkina Faso for example, the media focus on irregular migration is to be analysed as an echo of press releases from the Burkinabe authorities and international organisations working in the sector, which are largely focussed on raising awareness as to the dangers of this form of migration.

Surprisingly, the media seem to have largely ignored the effects of the Covid-19 pandemic on migration in the countries under review. The pandemic slowed down regular and irregular migration flows towards Europe, blocking thousands of people, especially seasonal workers, residents and temporary residents, and international students in highly precarious conditions. And inversely, since the pandemic caused borders to be shut it led to an increase in irregular crossings and a rise in fake news, especially in Colombia 6. Content with a negative tone has insinuated that migrants contributed to the spread of the disease. This discourse, combined with the fear of the virus spreading out of control, provoked xenophobic reactions in the country.

Training for journalists

The pandemic has nevertheless had an impact on the digitalisation of training courses for journalists as well as on themes covered. For example, the webinar “Migration and youth employment during the Covid-19 pandemic” in Senegal or the training course on “The impact of Covid-19 on migration, the legal migration channels and human trafficking” in Guinea, both funded by UNESCO.

Other obstacles to well-informed and well-balanced coverage of the topic of migration are:

- a lack of understanding of terminology with legal definitions (for example incorrect use of the term “refugee” instead of “immigrant”) and the use of adversely connotated terminology (such as the use of the term “clandestine” instead of “migrant person in an irregular situation”);

- difficulties gaining access to reliable sources of information, leading certain journalists to simply parrot information from European media;

- trouble gaining access to migrants, depriving journalists of primary sources of information. In several countries, journalists pointed out a paradoxical situation in which certain international organisations provide training on wellbalanced media coverage of migration, yet restricted journalist access to migrants and “controlled” what these persons say;

- limited newsroom interest for this theme (except when a drama hits the headlines) with the assumption that it does not appeal to the general public;

- a lack of financial resources to cover these topics which require time, travelling to zones where migrants are to be found and equipment to collect information. In places like Colombia, Burkina Faso and Jordan, there are also security aspects in that travelling to the zones in question can be risky;

- the lack of training for journalists on this theme. It is rarely included in their initial training and subsequently is addressed only in short courses for the beneficiaries of capacity-building projects.

Consequently, the media coverage of migration eludes certain sub-themes and is generally limited to purely factual coverage without in-depth examination of the issues. For example, in Morocco, 3.3 million persons are affected by emigration, i.e. 9% of the population. Yet the working conditions of Moroccans abroad are rarely covered, and news about them is often limited to the economic boost thanks to money transfers and returns in summertime.

The media also propagates stereotypes, to varying degrees from one country to another. In the Gambia for example, there are many social stereotypes of migrants in an irregular situation and returned persons who are deemed a “failure”. During the interviews, most interviewees stated that when the media address the issue of irregular migration and returns, people expelled from Europe and the USA are often described as “criminals”. Another illustration in Tunisia where the migration discussion group and the interviews conducted showed that the media coverage of migration topics contributed to the persistent “stigmatisation” of migrants from Sub-Saharan Africa.

Building capacity in the media on the theme of migration

Migration reporting skills are far from uniform in the countries under review. The extent of reporting skills varies according to educational resources within the countries under review. In Morocco, there is a Master of Research degree on “media and migration” and many capacity-building projects have been rolled out in the country, whereas journalists in Comoros have no access to vocational training locally (a single capacity-building project is known to have taken place between 2015 and 2021).

The table below recaps the number of capacity-building initiatives which have taken place in each country. These initiatives include a majority of training courses for media outlets on the theme of migration, as well as awards, financial and technical support for media output, the creation or reinforcement of journalist networks, think-tank workshop retreats, exchange visits to share experience etc. The Appendix on page 28 provides a non-exhaustive list of 208 capacity-building initiatives in the media which have taken place in the countries under review.

In terms of quantity, the report shows that there were very few capacity-building projects in certain countries, such as Madagascar, Jordan, Lebanon and Comoros.

In terms of quality, the report shows that the vast majority of the initiatives listed were short (one to three days), even if more formats have been available in recent years with more awards, networking opportunities, and even beginner training courses.

All the country reviews reveal that there is still great need for capacity building. The main pitfalls to be avoided to ensure that these actions have lasting effects are as follows:

- the training courses are too short: a single day of training does not lead to lasting change in how journalists work. Nevertheless, as journalists have emphasised in Tunisia, “getting a whole day off from newsroom work to take part in a training course remains a challenge”;

- the training courses only focus on theory: changing how journalists work involves the acquisition of technical skills (pushing back on fake news, datadriven journalism etc.), working on the ground and support during media production (investigative reporting, reportage etc.);

- the focus remains too frequently on very specific themes, especially irregular migration, to the detriment of other type of migration (diasporas, female migration, labour migration, student migration etc.);

- the same categories of beneficiaries are systematically targeted: the attendance not only of journalists, but also chief editors would be pertinent, since without their support, journalists cannot cover migration issues;

- the journalists’ initial level is not taken into account, with programmes containing inappropriate content;

- there is a lack of follow-up for beneficiaries: short- and mediumterm support and post-training follow-up in the form of mentoring is necessary to help media outlets in the longer term and to produce actual media content further to the capacity building.

Broader, longer-term support for the media is also necessary to ensure that the effects of these initiatives translate into media output. In Togo, for example, the topic of human trafficking is rarely discussed in the media despite the attention of the authorities and international organisations. The government, the International Organisation for Migration (OIM) and civil society organisations have regularly organised training workshops on this theme. Despite this and the effective participation of journalists in such workshops, very few results have been perceived in terms of the writing of articles and production of TV programmes on the topic given a lack of commitment, funding and long-term support.

North Africa

Migration trends

Morocco, Mauritania and Tunisia have historically been countries of origin, and are now becoming transit and destination countries.

These three Greater Maghreb states have been countries of origin for several decades, and still are in the 21st century. Boasting diasporas of hundreds of thousands of citizens, even millions for Morocco, the three North African countries under review in this report receive considerable financial contributions from their expatriates, up to 6.5% of GDP for Morocco.

In the past 20 years, North Africa has also become an important transit region for migrants, mainly from West Africa. Against a backdrop of human trafficking, especially via the “Libyan hell”, they head for the central Mediterranean area towards Italy or western Mediterranean countries such as Spain, including the Canary Islands. These irregular migration routes very often prove fatal: in 2021 alone, IOM clocked up over 2,000 deaths and missing persons in the Mediterranean, and over 23,800 since 2014.

Morocco is the most striking example of a transit country that has become a destination country. Proof lies in the two important regularisation drives involving tens of thousands of migrants in an irregular situation in 2014 and 2017.

During the most recent period, in 2020 and 2021, the Covid-19 pandemic slowed down the flow of both regular and irregular migration flows towards Europe, blocking thousands of people, especially seasonal workers, temporary residents, international students and people moving for medical care. Women migrants were harder hit during the pandemic: in Tunisia, for example, they not only lost more revenue than men but were also more vulnerable to the risk of sexual exploitation. 14

Migration issues in the media landscape

Excessive media coverage of irregular migration – with extensive coverage of tragedies, shipwrecks and crime, followed by periods without any media output – is produced to the detriment of other types of migration, like worker migration, family reunification and student migration. These are rarely covered, if ever, by the regional media. Despite their considerable size, especially in Europe, diasporas are hardly ever mentioned in the media.

Stereotypes and discriminatory language, playing on the fear of both settled migrants and those in transit, are regularly used in the written press and the audiovisual sector and on social networks, with the latter often amplifying misinformation, or fake news.

The NGO networks with a high level of investment on the topic of immigration, as in Tunisia and in Morocco, do sometimes manage to make their voices heard in the public debate, unlike migrants who rarely enjoy such opportunities and lack legitimacy to put their messages across in the public debate.

This partial media coverage of migration is to be examined against a backdrop in which investigative journalism is embryonic, with newsrooms under pressure from authorities, and lacking resources in general. Nevertheless there are some noteworthy exceptions, such as the websites Nawaat and Inkyfada in Tunisia, which are positioned as independent media outlets aiming to provide information on themes that are rarely addressed by mainstream media and thus contribute to the public debate.

Capacity-building initiatives

Tunisia has had a substantial number of workshops and training courses on migration for journalists. For over ten years, a great number of international organisations, NGOs and associations have offered training courses comprising both theory and hands-on sessions. The European Union and some countries like Italy and France were – and still are – among the most active sponsors.

These training courses have helped to introduce hundreds of journalists to migration issues. However, the beneficiaries are often critical of the nature of these training courses sometimes deemed too short, repetitive and too focussed on theory, without enough hands-on exercises. They also noted the lack of mentoring or follow-up after the course.

The impact of these training courses on the overall quality of media coverage in these countries is difficult to assess. However there is still plenty left to be done: not all journalists have a grasp of the basics of migration, and stereotypes and clichés still crop up in some media output.

West Africa

Migration trends

National data on migration is generally insufficient in West Africa and sometimes difficult to compare. IOM confirmed: “All reviews of migration emphasised major issues with shortfalls in the collection and production of data needed for a correct grasp of migration realities. The data available is patchy, making a full, detailed review impossible to conduct.”

Nevertheless, one generally applicable observation was gleaned from the countries under review in this section: the vast majority of migrants in West Africa circulate within the sub-region. According to UN data, in 2020, two-thirds of migrants from the region were living in another country in West Africa. This predominance of intraregional migration can be attributed to several factors, and especially the right to circulate without a visa between the member states of the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS) 19. Migration within the Community is primarily matter of mobility in the labour force. Those emigrating further afield usually head for Europe, often according to a long tradition rooted in history. These phenomena have led to diasporas, sometimes in excess of a million people, and contribute to the development of countries of origin by way of money transfers which may account for over 10% of GDP, as in Senegal for example

Irregular migration remains significant in West Africa. Since 2011, the route from the central Mediterranean region to Europe has been used ever more frequently. In the mid-2010s, the sea route to the Canaries also started gaining in popularity: the number of migrants crossing from West Africa towards the Spanish Canary Islands increased greatly in 2020, with 16,760 arrivals between January and November, i.e. an uptick of 1,000% compared to the same period in 2019. These crossings are particularly dangerous, since according to the Spanish NGO Caminando Fronteras (“Front-Line Defenders”) over 4,400 migrants (all nationalities taken together) either died or were lost at sea in 2021 during their attempt to reach Spain.

Because of conflicts and violence in connection with political strife, intercommunity and interethnic tension and extremism, most countries in West Africa are affected by internal and crossborder forced displacement, leading to a growing number of persons seeking asylum, even if the extent varies greatly from one country to another.

Lastly, environmental changes in West Africa are having repercussions on livelihood and human mobility, whether because of coastal erosion or variations in rainfall, as in Senegal, or drought within the continent, as in Niger.

Migration issues in the media landscape

As in Europe, irregular migration is, by far, the migration theme attracting the most coverage in West Africa. It is a recurrent feature on the news, with the occurrence of tragic events like shipwrecks, and other dramatic episodes on migration routes. An underlying trend gaining traction in recent years, of increasing numbers of women and unaccompanied minors in the irregular migration flows, has not yet been given the coverage it deserves.

One striking fact is that the media in countries with high emigration rates like Mali, Senegal and Burkina Faso rarely mention their diaspora or anything relative to worker migration in general. And yet this is the predominant form of migration in all countries covered by the report. The few media outlets addressing this theme do so from a very institutional vantage point, generally drawing on public discourse emanating from the authorities.

This lack of diversity in the topics addressed is combined with a more general observation involving all media taken together: there is an utter dearth of investigation and in-depth reportage on migration. The reasons cited – without doubt not the only reasons – are lack of time and means. Rather than in-depth investigation and analysis, media outlets are often content to publish press releases almost word-forword, as emitted by public authorities, international agencies, NGOs and associations, without stepping back to take a critical view.

While, in the best of cases, social networks and the internet may provide extra value, with influential bloggers who sometimes cover migration for example, they are too often a mere amplifier of bad practices, without filtering or considering ethics, simply repeating and amplifying clichés and stereotypes.

Capacity-building initiatives

While a number of capacity-building initiatives have taken place in this area, some countries have benefitted more than others.

Many needs still remain unmet, especially a thorough grasp of migration vocabulary and local, regional and transnational contexts, and the need to open up to the theme of international migration beyond the relative media hypertrophy with respect to irregular migration. Remarks by stakeholders, players and beneficiaries of training courses have generally been harsh, emphasising a deficit of detailed knowledge of migration issues. In short, specialist journalists are sorely lacking in all countries throughout the sub-region.

Indian Ocean

Migration trends

Migration trends in Madagascar and the Union of the Comoros, an archipelago in the Indian Ocean with a high poverty rate, bear the imprint of their historic links with France, as the former colonial power. Emigration of nationals from these two countries is strongly motivated by economic reasons, and France and its overseas departments are therefore one of the main destinations. Migration flows between Madagascar and the Union of the Comoros are also significant.

Labour and student migration account for most of the flow. Irregular migration and human trafficking, in particular for the purposes of exploitation via work and domestic service, frequently feature in the media, with coverage that leans into sensationalism while remaining superficial. Statelessness is a common phenomenon common in both countries, but is poorly documented despite potentially explosive consequences for living together in harmony. Lastly, while environmental migration is a mainly internal phenomenon for the time being, it is addressed regularly in the Malagasy media. This does not yet apply to the Union of the Comoros. The authorities of both countries have only recently started taking an interest in migration issues, exploited by politicians in Comoros, because of its proximity with Mayotte.

Migration issues in the media landscape

While the media landscape is very different in each country, in both their nature and modus operandi, the media coverage of migration issues have the same shortfalls. This report has revealed fact-based, superficial coverage, totally ignoring certain themes such as statelessness, and a lack of knowledge regarding terms and related concepts. Migration is often covered in the media of these two countries only as “hot” news, whether in reaction to tragedies or striking events, such as shipwrecks or the dismantling of human trafficking networks. Very little media coverage has any real structure or in-depth investigation as to causes and consequences or examination of different perspectives of migration phenomena.

Capacity-building initiatives

Few capacity-building initiatives on migration issues have been conducted in either country: one in the Union of the Comoros and seven in Madagascar. Training courses on human trafficking have been organised in both countries. Nevertheless, the initiatives already conducted seem insufficient to improve the structural quality of media coverage of migration.

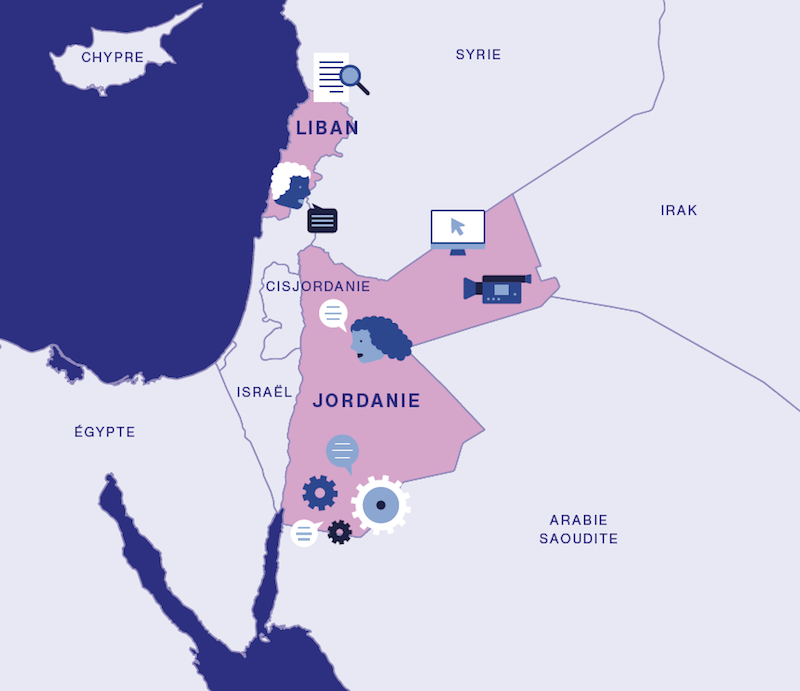

Middle East

Migration trends

Jordan and Lebanon are located in a region with various armed conflicts leading to a considerable number of forced displacements. Whereas neighbouring countries (Syria, Iraq and Palestine) have been greatly affected by recurrent conflicts in recent years, Jordan and Lebanon have enjoyed relative stability. Despite the uncertain political context, these two countries have had fairly similar experiences with migration:

- As refuges for the populations fleeing the war. Jordan and Lebanon have taken in successive waves of people forcibly displaced by various conflicts. Palestinians after the Arab–Israeli War (1948), Iraqi after two gulf wars (1991 and 2003) and, more recently, Syrians further to civil war in Syria (2011). In Jordan and Lebanon alike, these refugees account for over 20% of the population;

- As a destination country for migrant workers from Africa or Asia, both countries have had a similar experience and face similar challenges, especially with the sponsorship system (kafala) governing labour migration;

- Emigration is also a reality. Many Jordanian workers move abroad to seek out professional opportunities that they have not found in their country of origin. In Lebanon, emigration has even more significance, since the Lebanese diaspora is one of the largest diasporas in the world. The economic boost it affords Lebanon is considerable, especially when facing successive economic crises.

Migration issues in the media landscape

The two countries’ media landscapes are broadly similar, except for the multilingual dimension peculiar to Lebanon. Migration issues are perceived as sensitive in both countries and are mainly given sensationalist and negative coverage. Migrants are rarely interviewed, and the thrust of discourse is that of local or national authorities. There are frequent articles associating the presence of foreigners with economic, social and security problems in both countries. In contrast, the diaspora is viewed in a very positive light, especially in Lebanon.

Capacity-building initiatives

According to the non-exhaustive list in this report, both countries have hosted capacity-building activities in similar proportions in recent years: seven for Jordan and eight for Lebanon. Some activities have been specific to Lebanon or Jordan, others have been regional initiatives organised in Lebanon or Jordan for practical reasons. Given the migration challenges the two countries have to deal with, the volume of these initiatives has been deemed insufficient by people working in migration, as well as journalists.

Conclusion

They reflect the following guidelines:

- emphasise ethics and the code of ethics for the profession and the media in general (respect for terminology, data sources, diversity of viewpoints, image rights, etc.);

- address the question of migration in all its dimensions (emigration/immigration, grounds for migration, categories of migrants) and complexity;

- involve migrants in the design and/or implementation of capacity-building initiatives for the media;

- open up to more types of stakeholders taking part in capacity-building initiatives, either as beneficiaries, contributors or supervisors:

- for contributors, a smart move would be to involve people working in NGOs and academics working on migration issues;

- for beneficiaries, alongside the journalists it seems crucial to involve editorial managers and media directors as well as bloggers, but also to extend the beneficiary audience to journalists who do not speak French or English in the various types of media (including community radio stations);

- for supervisors, there is a need to organise training programmes for instructors and to identify national profiles/profiles from the sub-region;

- raise awareness among public institutions (national, local and regional authorities) as to the importance of ensuring the freedom of the press, independence of the media, data availability and statistics, so that journalists have access to reliable information.

Initial and ongoing training remains a key element to build reporting skills, but the setup (duration, format and journalists targeted) and themes must be more varied and shaped according to what has already been accomplished. Interesting practices can also be replicated, such as:

- training courses on the use of social networks: addressing how to adapt media outlets to these new platforms and designing modules to fight against misinformation and deter hate speech;

- training in data journalism and visual tools (graphs, maps etc.);

- the output and/or work from training courses and the setup of self-training and e-learning tools available online free of charge in the local language(s), accessible in formats suitable for mobile phones;

- mentoring schemes, especially to monitor output (articles, surveys, reports etc.);

- training courses which systematically combine theory with hands-on practice, with technical survey and investigation modules tailored to the migratory context of each country and visits on the ground in migrant hotspots (humanitarian camps, border checkpoints, regions or zones from which migrants depart, vulnerable zones involving human trafficking, campuses with foreign students etc.);

- training courses which specifically address ways of allowing migrants to have their say;

- decentralised in-person continuous training courses in various places rather than exclusively in capital cities:

decentralisation will make it possible to involve more local media outlets and integrate travel on the ground, preferably to places frequented by migrants;

- training courses intended for one type of media (e.g. written press or audiovisual media) because different media types don’t necessarily have the same training requirements;

- regional and interregional workshops with beneficiaries from several countries on a common theme (e.g. trafficking of domestic workers sent to Gulf states, mostly from Guinea, Comoros, Niger and Madagascar), as well as workshops attended by journalists from Europe, Latin America, the Middle East and Africa, as a way of harnessing different views and experiences;

- emphasise training for students in journalism and communication, working with universities and schools in each country, integrating migration issues in the curricula, as has been done in Morocco for example.

All the capacity building actions identified are accessible in the summary of the study.

Method

1/ Acknowledgements

First of all, we would like to thank all the interviewees for their availability and the quality of their contributions.

Management

This report has been drawn up under the supervision of Jocelyn Grange, Director for Africa, and coordinated by Hélène Brousseau and Mathieu Lebegue, Project Managers at CFI.

Editorial management

Astrid Robin, Head of Publications at CFI.

Steering Committee

Mickael Garry (MEAE), Marie-Hélène Guillerm (MEAE), Alison Larcher (MEAE), Émilie Oulaye (MEAE), Mélodie Beaujeu (AFD), Matthieu Burrati (AFD) et Florence Minery (CFI).

Proofreading and editing for harmonisation of the study

Mélodie Beaujeu et Mathieu Lebègue

Spell proofing

Elisabeth Gautier

2/ Authors

Country reviews for Burkina Faso, Comoros, Côte d’Ivoire, the Gambia, Guinea, Jordan, Lebanon, Madagascar, Mali, Mauritania, Morocco, Niger, Senegal, Togo and Tunisia by Red Mangrove Development Advisors.

Red Mangrove Development Advisors is a consulting firm providing support for players in international cooperation in both North and South.

3/ Coordination and international experts

Charles Autheman, consultant specialising in the media coverage of migration

Laura Denis, specialist in steering, monitoring and assessing projects

Barbara Joannon, specialist in the themes of migration and asylum

Thierry Leclere, journalist, film director and instructor, specialist in media coverage of international migration

Maïa Lê-Hurand, specialist in migration issues

Claire Neuschwander, specialist in steering and coordinating projects

Ophélie Tardieu, independent migration expert

4/ Local experts

Andjouza Abouheir Ali Ms, Country Analyst for Comoros

Elom K. Attissogbe, Country Analyst for Togo

Lilia Blaise, Country Analyst for Tunisia

Adama Bakayoko, Country Analyst for Côte d’Ivoire

Boubacar Koubia Diallo, Country Analyst for Guinea

Abou Dicko, Country Analyst for Mauritania

Bréma Dicko, Country Analyst for Mali

Jerry Édouard, Country Analyst for Madagascar

Mahamadou Kane, Country Analyst for Mali

Mouhamadou Tidiane Kasse, Country Analyst for Senegal

Salaheddine Lemaizi, Country Analyst for Morocco

Kouassi Combo Mafou, Country Analyst for Côte d’Ivoire

Amadou Mbow, Country Analyst for Mauritania

Tony Mikhael, Country Analyst for Jordan and Lebanon

Haingonirina Randrianarivony, Country Analyst for Comoros and Madagascar

Bubacarr Singhateh, Country Analyst for Gambia

Lamine Souleymane, Country Analyst for Niger

Gulnar Wakim, Country Analyst for Jordan and Lebanon

Romaine Raïssa Zidouemba, Country Analyst for Burkina Faso

5/ Country review for Colombia

Dara International was founded in 2003. It is an independent nonprofit organisation committed to improving the quality and effectiveness of humanitarian response and development aid by assessing and measuring the impact of initiatives. Its quantitative and qualitative reports help governments, UN agencies, NGOs and other civilian stakeholders to make decisions on policies, strategies and programmes based on solid data.

6/ Coordination and experts

Gilles Gasser, freelance journalist and consultant, specialising in communication and information management issues in humanitarian response, especially in the regions of the world having to deal with migration

Silvia Hidalgo, economist, analyst and assessor specialising in the assessment of humanitarian and development aid