Digitial Citizenship: what's happening in Africa

Benin - Burkina Faso - Ivory Coast - Democratic Republic of Congo - Ghana - Madagascar - Senegal

Download the summary of the study (PDF)

Télécharger l'étude complète (PDF)

INTRUDUCTION

In sub-Saharan Africa, access to social media has made civil society louder and more visible. In the seven countries featured in this report (Benin, Burkina Faso, Ivory Coast, Ghana, Madagascar, the Democratic Republic of Congo and Senegal), ordinary citizens are becoming freer to make themselves heard, popular initiatives are multiplying in areas where state action is in short supply and we are witnessing the emergence of key figures ("opinion formers") capable of influencing popular debate, not least due to their social media followings.

In this new environment, election times are tense moments – especially since the 2012 elections in Senegal, which showed how citizens grouped around a handful of activists could organize an alternative count of the votes by attending large numbers of polling stations and publicising the results via text messaging or social

media.

In recent months, the frequent blocking of access to Facebook, or of internet access as a whole, in sub-Saharan Africa provides additional evidence of the important role that social media have taken in the circulation of news. Governments are succumbing to the temptation to criminalise their use. Zimbabwe has already begun drafting a cybercrime law that puts freedom of expression under threat. It is to be feared that other countries will be tempted down the same road in the months to come. A growing number of institutions and public services are meanwhile putting themselves on Facebook and tackling the tricky business of direct dialogue with citizens online.

In Dakar, Abidjan, Bamako and Kinshasa, citizens are taking action to gather, produce and disseminate news on the web, playing an increasingly active and significant role in public debate.Conversations that begin on social media (essentially Facebook and WhatsApp) are having an increasingly substantial impact. In Ivory Coast, they led the head of state to announce the abandonment of measures to put up the price of electricity. In Senegal, the building of the Turkish embassy on a public stretch of coastline had to be called off.

This on-the-ground study was carried out in May and June 2016, with the help of local correspondents in seven countries. In each one, an initial outline of the environment and key players in online civic action was followed up by a series of interviews and an investigation in the field. A selection of activists and observers in other countries, such as Cameroon and Mali, were also interviewed.

A total of 41 people participated in the study.

The vast majority are activists and participants in the online civil society of sub-Saharan Africa. Various industry experts were also asked to contribute.

At the same time as being closely involved in debates in their own nations, these highly engaged web users enjoy tight cross-border connections and share their experiences in real time, creating a sort of pan-African club of cyberactivists. The "

Africtivistes" network is just one of the specific forms this transnational movement has taken.

THE DIGITAL STATE OF PLAY

MOBILE PHONES FOR ALL

It may be firmly at the bottom of international rankings for access to digital technology as a whole, but Africa's adoption of some technologies is advancing fast.

One of the most significant changes is the rise of mobile telephones. In the space of the last decade, using a mobile phone has become an everyday part of life in the majority of African countries, thanks largely to falling equipment costs and the competition caused by the proliferation of telecoms providers.

Now that they are offered a choice, users readily purchase multiple SIM cards to enjoy each operator's best tariffs and promotions. In some countries, the rate of mobile phones per head of population may even go beyond 100%.

In 2014, Benin, Ivory Coast, Ghana and Senegal all had more than one mobile phone per person.

THE SLOW TAKE-OFF OF THE INTERNET

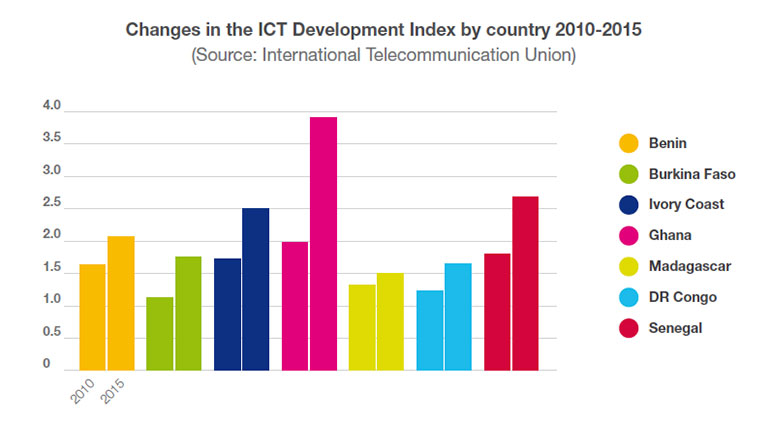

Modelled on the Human Development Index used by the

United Nations Development Programme, the ICT Development Index (IDI) has been developed by the International Telecommunication Union to measure the health of the ICT industry. The IDI ranks progress on a scale from 1 to 10 in four areas: the level of ICT development, progress over time, reduction in the digital divide and the potential for future growth.

Data published by the ITU in its latest report reveals that, despite the progress recorded in recent years, African countries are moving forward at a slower rate than other geographical regions.

Nevertheless, progress in Africa is continuing apace and solid investment is needed to recover the lost ground.

In terms of accessibility, the countries covered by our report fall into two groups:

>> Those where the proportion of the population with home internet access via a computer, mobile or tablet has passed the 20% barrier. This group comprises Ghana, Senegal and Ivory Coast.

>> Those where less than 10% are online: Benin, Burkina Faso, the Democratic Republic of Congo and Madagascar.

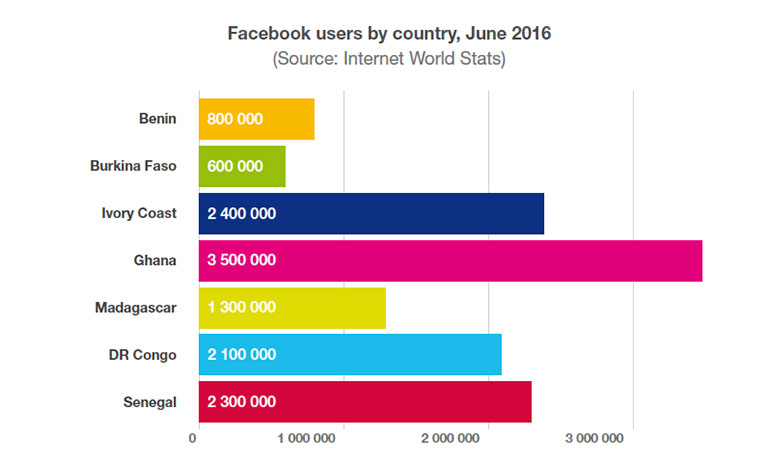

FACEBOOK: SYNONYMOUS WITH THE INTERNET FOR NEW WEB USERS

You don't need a computer or even an email address to open a Facebook account and enjoy the main services offered by the US giant. A telephone number is enough. Through its

Zero Facebook mobile site, the social network also allows its principal features to be accessed free of charge.

Users can update their status, check their feeds, comment on posts and send and receive messages, all from their mobile phone. Making access easy in this way has enabled Facebook to achieve phenomenal growth in just a small number of years.

Without Facebook, there is no doubt that the internet would not have the same appeal for the new web users who arrive online every day in sub-Saharan Africa. The social network has become the destination of choice to find out what's going on, connect with family and friends, do shopping and chat.

ACTIVIST PROFILES

THE "CITIZEN ACTION" GENERATION

Francophone Africa's first online civic activists appeared around a decade ago, taking their first steps online (often by starting blogs) between 2005 and 2010.

For example, this was the time when Senegalese high school student

Cheikh Fall began to put his lessons online to share what he was learning with his contemporaries, although few of them had access to the web at this point.

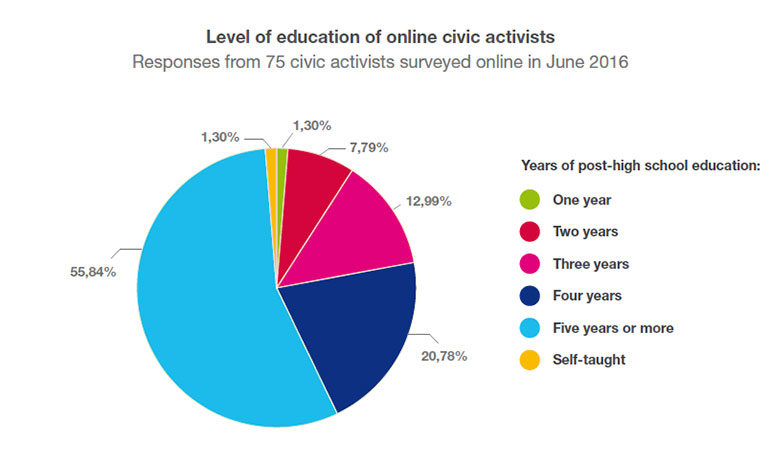

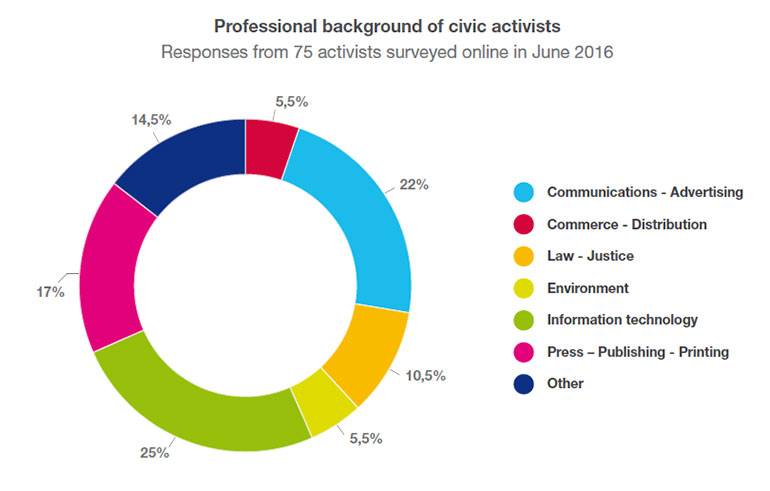

When you look at the online civic action community and meet the people behind the activities, the first thing that strikes you is their level of education: the majority of activists have pursued advanced university studies (high school + 5 years or more).

The majority of citizen activists we met in the course of this study talked about a mission in which they felt invested. Their engagement owes little to chance, being due instead to a conjunction of technological opportunity with deep conviction. The underlying motivations take a variety of forms.

For Mylène Flicka in Benin, the impetus came from an internship at the country's Ministry of Foreign Affairs: “I had the greatest disappointment of my life from the slowness of the administration, the methods they used and the whole panoply of little administrative errors they made."

Cyriac Gbogou, from the Ivory Coast, explains that “I found it frustrating that the press stayed silent when strikers were put in jail or murdered by the forces of law and order. That's when I discovered it was possible for citizens to use the internet to share news and use photos and video footage to support it."

EDUCATED ACTIVISTS BECOME TRAINERS FOR OTHERS

Being in possession of a sound professional training, some of the activists we met, especially the older ones, attach particular importance to the question of training their fellow citizens. Sharing knowledge and skills forms a part of the digital activist's behaviour.

For Joël Nlepe in Cameroon, it's a matter of

"opening people's eyes, so that you say: this is what's happening with where the world is going."

The place of women in society is also a key issue. Although women generally form a minority in events or activities involving new technology, there are a large number of initiatives afoot to reverse that trend.

In Senegal, Jiggen Tech, Awa Gueye's Jiggen Tech incubator is helping women to learn about IT: “The women here have a variety of backgrounds, but what they share is that everything they do is linked to technology. With the Jiggen Tech incubator, we are giving training in schools all over the place, from the youngest in the sixth form onwards, to teach them about coding and everything to do with IT, which makes it possible for girls to aim to pursue a scientific education after they leave school."

ACTIVIST PORTRAITS

KINNA LIKIMANI

Kinna Likimani uses technology to break down different forms of exclusion. Of Ghanaian and Kenyan origin, this 40-year old feminist blogger was the founder of Ghana decides, a project which used the internet and social media to monitor Ghana's 2013 presidential election and its coverage in the media. Likimani takes grassroots action to make sure decision-makers take account of the aspirations of people who lack access to the web.

CHEIKH FALL

A Senegalese

blogger and cyberactivist, 34-year-old Cheikh Fall was the founder of #Sunu2012, a platform for the popular monitoring of Senegal's 2012 presidential election. He is currently working on building up a network of activists from different sub-Saharan African countries via the Africtivistes collective. Fall is convinced that the clever use of technology can alert and inform, as well as putting pressure on the leaders of countries hostile to public debate and the idea of accountability.

LARISSA DIAKANUA

LARISSA DIAKANUA

This 33-year-old Congolese journalist and

blogger sees the internet and social media as tools for making yourself heard and gaining access to things that people in a country such as the Democratic Republic of Congo need to know. She believes that “Freedom of expression is easier on the internet. You can say what you think without fearing the censorship and pressure exerted over traditional media." In her blog posts, she makes use of this relative freedom of expression to, as she says, “talk about Congo as it really is and point out society's failings so that we can try to change how people

think."

CYRIAC GBOGOU

Since the Ivory Coast's post-election crisis in 2011, this 36-year-old

activist has been involved in every online civic action in his home country. In January 2013, Cyriac and fellow blogger Mohamed Diaby were arrested by the police: after deaths had occurred in a crush around a stadium in Abidjan, the two bloggers sought to count the number of victims and provide information to families searching for their loved ones. This activity was not to the taste of the authorities.

INFRASTRUCTURE

A poor relation in terms of available bandwidth, Africa is working hard to close the gap with the rest of the world. Whereas globally the rate of growth in capacity is slowing (rising by a mere 31% in 2015 relative to the year before), annual growth in Africa has averaged 51% over the past five years. The arrival in Africa of ACE, SEACOM, EASSy, WACS and other new transoceanic cables is prompting internet giants such as Google to locate cache servers on the continent so as to reduce costlier long-distance web traffic.

Internet charges remain high

Accessibility remains a fundamental issue in many of Africa's countries. The main constraint pointed out by the persons interviewed during this study is cost-related. In Benin, for instance, digital activists complain about the very high charges levelled by operators for internet use.

In June 2016, price rises (of up to 500% for some charges) triggered protest movements in the Democratic Republic of Congo. Consumer mobilisation forced the government to intervene to bring prices back down to the previous level, which was already high in comparison to the regional average.

Users in all the countries covered by this study highlighted the difficulty of obtaining access outside the capital or major cities.

MOBILES AND SOCIAL NETWORKS

THE UBIQUITY OF MOBILES

The number of unique mobile subscriptions in sub-Saharan Africa has risen by 18% per annum over the last five years.

GSMA, an association of mobile phone operators, noted in a 2013 report that growth in the region was the highest in the world. The ubiquity of mobile telephones must not be allowed to conceal the fact that usage differs between the owners of smartphones, feature phones and basic devices that can only be used for audio calls and text messaging.

Social media sites record more visits than news sites

However, analysts' forecasts of increasing smartphone penetration in sub-Saharan Africa allow us to see an expansion in the number of web users with mobile internet access. Massive sales of midrange Chinese smartphones costing under $200 are enabling new segments of the population to arrive on the net each year.

Usage habits are being transformed by the massive use of mobile devices and a marked enthusiasm for social media. In the face of interactions on Facebook and, to a lesser extent, Twitter and other communications platforms, electronic messaging and visits to news sites are becoming secondary activities.

THE CENTRAL ROLE OF FACEBOOK

Facebook's status as the preferred social network is due not least to the fact that it is relatively easy to create groups and link users together around a cause or a regular event. In places where the freedom of expression and association is repressed, Facebook groups represent a genuine alternative providing a virtual space for debate.

In Burkina Faso, the official website of the Gendarmerie Nationale, which has over 43,000 members, suggests that it aims to “provide citizens with better assistance in their security". In Ivory Coast, contacting the police by phone has repeatedly proved less effective than posting a message on the “Police Emergency" Facebook group, whose members include firefighters and police commissioners.

Facebook and social media generally are becoming unavoidable for businesses, public figures and institutions, who are moving into these shared spaces and using them as a means to interact with the public. Social media are also taking centre-stage in the political landscape, where politicians, both individually and in conjunction with their parties, are using them to spread ideas, form and consolidate communities and persuade future voters.

THE SUCCESS OF WHATSAPP, VIBER AND SNAPCHAT

As Beninese journalist Vincent Agué stresses, the rise of WhatsApp mirrors the democratisation of the mobile phone. “Now that cheap smartphones are available on every street corner for less than 30,000 CFA francs (approx. €50), using popular mobile apps is no longer the preserve of a handful of wealthy people or enthusiasts. Because of WhatsApp, which appeals to an ever growing number of users, people now prefer to incur an internet use charge on their phones for WhatsApp messaging than pay for traditional texts. “Wazzap", as it's generally pronounced, is how people chat with their contacts now."

This phenomenon affects every country in our study, even if the company, a subsidiary of Facebook, has not yet published any figures. Free messaging and the promise of end-to-end encryption for your conversation are also factors that make it popular with Africa's young mobile web users.

Widespread use of WhatsApp will not be without its downsides, not least of which is the spreading of rumours and disinformation under the cover of anonymity. The dissemination of rumours and false information accompanied by the phrase

lu pour vous (“your digest") was mentioned in several countries.

“Public chats" on Viber

The

Viber messaging app, a direct competitor of WhatsApp, is also experiencing growing success, although here too it is difficult to value it or put it in figures. The app claims to have 664 million users around the world.

One notable

One notable feature of Viber is the launch in Africa of “public chats".feature of Viber is the launch in Africa of “public chats". These allow media providers or individuals validated by the platform to share information with audiences that can reach substantial numbers.

For example, the website

allafrica.com has over 100,000 followers for its tchat public. In Senegal, the Seneweb portal has 3,500 followers. The internationally famous Senegalese musician Youssou NDour has 171,000 followers. And 11,500 people follow Africa goes digital (in French, despite its name), a public chat on Africa's online evolution involving around 30 African contributors.

Snapchat is gradually taking off amongst young people under 25.

Communities are rapidly developing, such as

African Trip, which grants the keys to a Snapchat account to a different person each day to introduce others to their lifestyle and express their reactions to the news.

SPREADING THE NEWS

QUALITY

The explosion in user numbers and growing interest in social media have had significant repercussions on the production and consumption of news.

Social media also allow citizens to address political decision-makers directly.The era of state media monopolies has been well and truly overthrown. As the use of digital forms advances, traditional media – the press, radio and TV – are now having to adjust to the entry on the scene of amateur news providers and the emergence of new channels of broadcasting.

Citizens, previously confined to the role of spectator, now play an active part. Even when they don't produce content themselves, they can comment on, supplement or dispute the news produced by professional journalists. Social media also allow citizens to address political decision-makers directly. These profound transformations are raising questions about plurality and quality in the news, as well as about the impact on citizens, journalists and political figures of the drive towards instant reaction.

Traditional media lagging behind

All of the activists we interviewed complained about a lack of responsiveness from the traditional media, which are lagging behind an audience that craves immediate reaction. This is giving free rein to amateur news providers with the attendant risks of inaccuracy and confusion, not to mention the ethical questions such problems raise.

Ivorian journalist and blogger Israël Yoroba Guebo recalls: “When the terrorist attack occurred at Grand Bassam on 13 March 2016, the traditional media didn't arrive at the scene until several hours after the event. The news was essentially reported by eyewitnesses. Ultimately, there was more reaction from ordinary citizens than from professional journalists. Yet this posed problems with regard to the credibility of the news that was being reported and with regard to ethics, which underlined the need for the traditional media to adapt to these changes in consumer habits."

The news flows that pour into social media are widely shared. But the quality is not always up to scratch. Social media and instant messaging apps also serve as conduits for the propagation of rumours. Whilst they are certainly platforms for discussion in which ideas can circulate freely, the detrimental effects these instruments can have underline the need to strengthen the production and circulation of high-quality news.

The spectacular growth of online media in the countries of sub-Saharan Africa is giving rise to a competitive situation – a race for the news – in which participants regularly fall by the wayside. In 2013, a bug on the abidjan.net portal caused a two-year-old article on a plane crash to be republished. The news was immediately picked up by social media users and some media providers, until the blogger Cyriac Gbogou finally put an end to the misinformation by posting an article on his blog.

Different national communities have adopted hashtags to collect conversations about their countries on Twitter, generally at the instigation of bloggers. In Ivory Coast,

#Kpakpatoya, from a word meaning “gossip", is the one that dominates. In Senegal, it's #Kebetu, which is Wolof for chat, natter, or shoot the breeze. In Benin, it's #Wasexo, which literally means “come and hear me speak".

Les différentes communautés nationales ont adopté des hashtags pour rassembler les conversations liées à leur pays sur Twitter, généralement à l'initiative de blogueurs. En Côte d'Ivoire, c'est

qui s'est imposé. Le mot signifie

commérages. Au Sénégal, c'est . En wolof, cela veut dire parloter, bavarder, causer. Au Bénin, c'est qui signifie littéralement "venez entendre parler".

Traditional debate expressed online

Behind these keywords, which form a kind of virtual curtain behind which web users from each country can congregate, a common reality is apparent: comment and debate on the news (the traditional

“titrologie" beloved of Ivorians) have found a new space for expression online.

Nevertheless, on closer inspection the hubbub of conversation masks a reality that is less easily unveiled. In Senegal, whilst there may be no censorship per se, self-censorship definitely exists, as

Alexandre Gubert Lette remarks:

“Yes, people do talk a lot, but there are some subjects they keep quiet about. It's as if we had a straightjacket round our minds. No one goes near the issue of Islamic brotherhoods. There's a sort of tacit consensus that says, that's something you don't talk about. And in my opinion we don't talk too much about women's rights either."

When bloggers filter the news

Such curation is a task that usually falls to the media. When terrorists attacked the beach at Grand Bassam, 40 kilometres from Abidjan, national television didn't bother to inform its viewers of the events until a little before 8 pm, by which time international news channels had been running special edition coverage of it for several hours.

Ivorians were putting out all kinds of news on social media. One group of bloggers got together immediately to filter the content that was circulating, alerting people to the lack of verification and trying to cross-check reports from witnesses. By contrast, several Ivorian newspapers did themselves little credit when, the day after the attack, they published front page photos that had nothing to do with the events.

MORAL AND ETHICAL RULES

Whilst the democratisation of mobile telephony and the mass adoption of social media are making news easier to obtain, the challenges regarding the quality of the news remain undiminished. Whether it is broadcast on the radio, on a website or via a mobile app, the credibility of the news needs to be ensured, which means it must be gathered and handled in accordance with a number of moral and ethical rules.

For journalists:

Responsible, professional media providers can serve as upholders of the public interest. However, professional and ethical journalistic practice requires high-quality training. Basic training is thin on the ground and its quality is erratic.

The short cycles of general or thematic-based training sessions offered by international organisations do not suffice to meet all needs. As a result, journalists on the whole get their training on the hoof. While those who find themselves in a newsroom may benefit from the guidance of more experienced journalists, the freedom of expression of journalists online is unfiltered by an editor-in-chief, which exposes them to the risk of sensationalism.

Many thus succumb to the temptation of picking up the unsourced content and unverified information that circulates widely

on social media.

For bloggers:

Bloggers are newcomers to the field of news. Not all of them are journalists and not all are conscious of the responsibilities they bear when they speak out in public. The cultural standards rooted in press law, such as respect for privacy, the presumption of innocence and the avoidance of defamation, are often lacking, such that they are tempted through ignorance to cross the red lines that the law sets.

For the general public:

The progress made in recent years in terms of pluralism and diversity of sources puts the spotlight on new challenges, especially as regards how to interpret the unending flow of information deposited on social media. The difficulty of telling true news from false news is among the shortcomings that have been noted in internet users who discover the web in the social media age.

This is where news commentators come into play, since they have a key role in validating the most widely shared content. Such people may be journalists or simply the moderators of online communities; they deserve special attention in view of the responsibility they bear. Being better equipped, they can contribute to reducing the rumours and misinformation that spread widely on social media.

CITIZEN PARTICIPATION

The social upheavals seen in recent years in francophone Africa and the emotion they unleash form a wellspring of civic action. The regular floods that hit certain parts of Dakar or problems with access to basic healthcare are unleashing solidarity movements that start on the web before transforming in some cases into fundraising campaigns or public demonstrations.

As Joël Nlepe remarks in Cameroon, “You can mobilise people if a woman has spent a long time outside the hospital waiting for surgery when there's a doctor inside. On the other hand, it's hard to mobilise them by saying, 'Wear black to protest against the President running for a new term in office'. […] When something touches on people's well-being, it's very specific, so then you have a chance of mobilisation."

Emotion is the spark of mobilisation

Mobilising citizens to help the sick is one of the commonest forms of action in several countries. In Ivory Coast, several fundraising appeals have been launched to raise money for drugs or surgery for people whose fate has moved the bloggers. The

#CIVsocial hashtag, launched in violent and unstable times in 2011 when the country had just emerged from civil war, has been used on a number of occasions to help such people.

Cyriac Gbogou recalls, “During the first collection we organised to buy drugs for a child, I went to collect money from the homes of people who were offering to donate. The first person was on the other side of the city and I spent 3000 CFA francs on a taxi fare for a 1000-franc donation. I was a bit disheartened, but by the end of the day we'd collected 800,000 francs, which was enough to buy the drugs."

An emotional response can also be triggered when people are granted special privileges.In Senegal, the construction plans for new buildings to house the Turkish embassy on the western Corniche were the trigger for a large movement that resulted in demonstrations.

Issues linked to internet access are also liable to mobilise the inner circle of online civic activists. In the Democratic Republic of Congo, an

online campaign was launched in June 2016 to fight against rises of up to 500% in charges for access to the web. The campaign's aim was for the government to simply annul the new price list that the campaigners regarded as abusive. Mobilisation in the streets in the wake of the online campaign ultimately forced the government to intervene and oblige the operators to revert to their previous tariffs.

Activism development

Networks of citizens develop in different forms. Among the most influential and organised groups in the majority of African countries are bloggers' associations, which play an anti-establishment role and are often regarded as hotbeds of opposition.

Senegal has one of francophone Africa's most active communities of activists, in which groups with different outlooks often join forces to launch campaigns. The origins of this activism can be found in the success of the election monitoring movement

#Sunu2012,, which mobilised people to take part in the popular monitoring of the voting during the 2012 presidential election.

As Cameroonian journalist Edouard Temba notes, “When you talk about civic activism, you're regarded as part of the opposition." Online activists sometimes play the role of ambassadors, giving voice to the complaints of fellow citizens who lack a presence of their own in the online channels provided by social media. Civic activism and the organisation of online movements often has the effect of causing activists to be classed as opponents of the regime.

SOME EXAMPLES OF ONLINE COMMUNITIES

Here are a few examples from amongst the many civic action communities that have formed online. They provide an illustration of the conversations being held on Facebook, the main platform used to mobilise participants.

>> Groupe Jeunesse consciente (Democratic Republic of Congo) - 190,000 members “Conscious Youth" – a Facebook group for news and discussion on Congolese current affairs.

>> Groupe police secours (Ivory Coast)- 41,000 members

The “Police Emergency" group is a Facebook group whose members include police commissioners, firefighters and other emergency workers, covering road accidents, hitand-runs and corruption issues.

>> Communauté Facebook pour lutter contre l'indiscipline des Sénégalais (Senegal) - 31,000 members

“The Facebook Community to Combat the Indiscipline of the Senegalese" decries the behaviour of drivers who ignore the rules of the road and people who dump rubbish where it doesn't belong.

>> Communauté Facebook “Méritocratie malienne" (Mali) - 36,000 members

“Malian Meritocracy" rejects patronage and graft in favour of merit-based recruitment and promotion.

OPEN GOVERNANCE

As unavoidable tools of communication, social media now occupy a central place in the political landscapes of the countries we surveyed. Political figures are increasingly present on the main communication platforms and strive to form and consolidate online communities.

In the Democratic Republic of Congo, restrictions on the access of opposition figures to state media and the pressure placed by the government on private media organisations mean that social media represent the sole alternative for public expression for dissenting voices. The most violent, but also the most interesting, exchanges between opponents and members of the government now takes place on social media.

The most interesting exchanges are on social media

Ahead of Benin's most recent presidential election, the country's internet users were able to put questions on youth employment to Prime Minister

Lionel Zinsou via the hashtag #gouvernerautrement, an attempt to engage in direct dialogue with the public inspired by Barack Obama's “Ask Me Anything" threads. The election itself, which took place a few months later, was the occasion for debate between the candidates and personalities who had emerged on the internet and social media.

In the view of journalist Maurice Thantan, this was an encouraging sign:

“This bodes well for the future, because the opinion formers are increasingly being listened to and will thus compel the state authorities to make changes. When you see presidential candidates talking to web users in the context of a general debate, that's a sign that the internet already reaches a large number of people."

Ivorian journalist and blogger Daouda Coulibaly, however, strikes a cautionary note: “Thirty-one of the thirty-six ministers that make up the current Ivorian government run Twitter or Facebook accounts. But you can count on one hand the number who really engage with the public."

Governments and other public services also maintain a presence on the main platforms, particularly Facebook and Twitter. Citizens may expect more openness, transparency and dialogue from their governments, but governments themselves see social media strictly as one-way channels. Governments who establish a genuine dialogue with the governed are rare.

Official accounts are usually handled by communications departments, who are skilled at publishing content but not at issuing official responses in the name of the account holder.

PARTICIPATION IN LAWMAKING AND GOVERNMENT DECISIONS: BENIN'S “COLLABORATIVE GOVERNANCE PROGRAMME" (PGC)

In Africa, popular participation in the drafting of laws and regulations is still in the realms of science fiction. Yet in Benin, active citizens such as the

No Limit Generation (a community group for socially engaged youth), together with online “directory of young stars" Irawo, the Benin Creative Collective (CCBENIN) and software developer OlaSoft have started an initiative whose results will be closely watched. In February and March 2016, during the presidential election campaign, the Collaborative Governance Programme (Programme de Gouvernance Concertée) sought to gather ideas for the country's next elected government. Five hundred of the ideas collected were to be selected and put to the new administration.

Conducting politics on the internet is nothing new in Benin, where a Facebook group called the

“Benin Virtual Government" has 12,746 members. Established in 2012 by Dine Adechian and a number of other Beninese activists, the group's stated objective is to run the “Virtual Republic of Benin".

Members of the group post comments on national current affairs, while it also serves as a forum for publicising job vacancies and training opportunities. As a laboratory for civic and political initiatives, it aims to contribute to dialogue between the generations and familiarise young Beninese with the operation of the republic's institutions. The group also organises monthly sports and health days in Cotonou.

SEARCHING FOR A BUSINESS MODEL

Earning revenue is not the primary motivation for any of the civic activists we met. Nevertheless, the ability to put financial resources to work is often key to getting effective and long-lasting ideas

off the ground.

With no expectations of funding from national or international backers, the activists have been able to mobilise their online communities to raise funds for humanitarian causes, for instance via the #CIVsocial hashtag in Ivory Coast since 2011 or the #SunuCause hashtag in Senegal since 2012. The money has been collected manually or through mobile payment systems.

Online funding efforts

Using crowdfunding platforms was never contemplated during these fundraising efforts. The need to have a bank card remains a difficult obstacle to overcome for the majority of the continent's inhabitants.

In the absence of a third party to guarantee that funds are properly used, activists have taken great care to be transparent. They have publicly given personal thanks to each donor and kept detailed and open records of their spending.

International backers such as

OSIWA (Open Society Initiative for West Africa) have since contributed to the funding of a number of election monitoring activities in various countries.

Ensuring financial independence

It remains the case that the sustainability and professionalisation of activists' work depends at least in part on their ability to generate financial resources over the longer term. It should be noted that the skills that activists succeed best at monetising are those they acquire in the course of creating online popular initiatives. Their community management capabilities are eyed with interest by politicians, businesses and major brands. Their social media audiences also give rise

to plenty of inquiries.

Over the next few years, the question of the financial independence of civic activists is set to become more important. The need to assure their independence by generating sustainable financial resources will be one of the major challenges they have to face.

CONCLUSION

In Africa, as elsewhere, the rapid adoption of the internet and social media by individuals and (at a slower pace) by media providers, businesses, state institutions, NGOs, CSOs and other organisations is rapidly and profoundly reconfiguring the public arena.

Citizens now produce, comment on and circulate content themselves, giving them an unprecedented ability to express their views, make themselves heard and organise at little financial cost. This situation is generating unprecedented opportunities and hopes in the seven countries covered by this study, but it is not without risk.

Access for all to public self-expression and the ability to share knowledge coexist with disinformation and the fear of universal surveillance.

The embedding of democratic practices in the countries we have examined is being achieved not only by strengthening the capabilities of journalists and media providers so that they can fully embrace digital tools, but also through the rise of a large number of new active citizens who have already shown, especially in the context of elections, the positive role they can play.

Issues related to the quality and diversity of news in these countries, to the transparency of state action and institutional accountability are intimately linked to the existence of a structured environment that encompasses journalists, bloggers, IT developers, government representatives, data and mapping specialists, NGO and CSO members and others besides.

Assisting Africa's citizen activists in the development of an open, pluralist, participative and wellinformed

public arena currently represents a challenge with a number of different facets:

>> Contributing to the improvement of access to information (hence also access to the internet)

>> Familiarising people with issues relating to digital society and popular participation

>> Supporting news and data providers in service of public debate

>> Structuring national/international networks and local ecosystems of activist citizens

>> Developing a culture of open state data and the uses to which it can be put

We are at a historic moment at which history is continuing to hesitate: digital technologies are opportunities for openness and debate, but also for surveillance and censorship. Which way will the scales fall? Popular activists today are at the vanguard of the battle to make the internet and social media into means for embedding the construction of democracy and inclusive development in sub-Saharan Africa.

COUNTRY PROFILES

GLOSSARY AND SOURCES

Cyberactivists: Term covering various forms of militancy practised with the aid of the internet. Africtivistes, the African association of cyberactivists for democracy, held its first meeting in Dakar in November 2015.

Open data: Open data is both a movement, a philosophy of access to information and the practice of publishing data so that it is freely accessible and usable. It forms part of a trend whereby state information is regarded as a common good whose dissemination is in the public interest.

Open Government Partnership (OGP): The Open Government Partnership is a multilateral partnership which aims to promote transparency in government activity and open it up to new forms of collaboration and joint action with civil society, in particular through the exploitation of digital and other new technologies. The OGP is run on a collegial basis involving both governments and civil society. The presidency of the organisation is currently held by France, for a one-year term which began in September 2016.

Democracy Index: Founded by the Economist Group in 2006, the Democracy Index assesses the level of democracy in 167 countries. Evaluations are based on 60 criteria grouped into five categories, namely electoral process and pluralism, civil liberties, functioning of government, political participation and political culture. Countries are scored on a scale from 0 to 10. Each country is then classified as a full democracy, flawed democracy, hybrid regime or authoritarian regime according to its score.

World Press Freedom Index: Reporters Without Borders, 2016

Measuring the Information Society Report: International Telecommunications Union, 2014

Youth Transforming Africa: World Bank, May 2016

Youth employment in Sub-Saharan Africa (Vol. 2): World Bank, January 2014

Evaluating Digital Citizen Engagement: World Bank, February 2016

Africa Energy Outlook: International Energy Agency, 2014

Sub-Saharan Africa Mobile Economy 2013: GSMA, 2013

The Global Information Technology Report 2016: World Economic Forum, July 2016

Numérique au Sénégal, état des lieux et perspectives 2010-2016: Romain Masson, July 2016

AUTHORS OF THIS STUDY

Cédric Kalonji

A journalist to

radio Okapi & RFI, and new media expert, Cédric Kalonji is also a trainer and an acknowledged expert in helping African journalists and media providers to embrace online channels.

Philippe Couve

Philippe Couve is a director of Samsa.fr and a former journalist (RFI, Atelier des médias). An international expert in the digital transition of media providers and media entrepreneurship, he has been working for ten years to promote the emergence of a new generation of African journalists and bloggers.

Julien Le Bot

A journalist and filmmaker specialising in editorial development and open data,

Julien Le Bot works as a consultant on media innovation projects and helps run incubator schemes for the founders of digital media projects. Since September 2016 he has been the presenter of RFI's

"L'Atelier des médias".

Contributors

Benin -

Sinatou Saka

Burkina Faso -

Justin Yarga

Côte d'Ivoire -

Cyriac Gbogou

Ghana -

Edward Amartey-Tagoe

Madagascar -

Lalatiana Rahariniaina

RD Congo -

Yves Zihindula

Senegal -

Lucrèce Gandigbe

With

Ange Kasongo

Mansour Abderahmane

et Marianne Rigaux